Jide Akintunde, Managing Editor/CEO, Financial Nigeria International Limited

Follow Jide Akintunde

![]() @JSAkintunde

@JSAkintunde

Subjects of Interest

- Financial Market

- Fiscal Policy

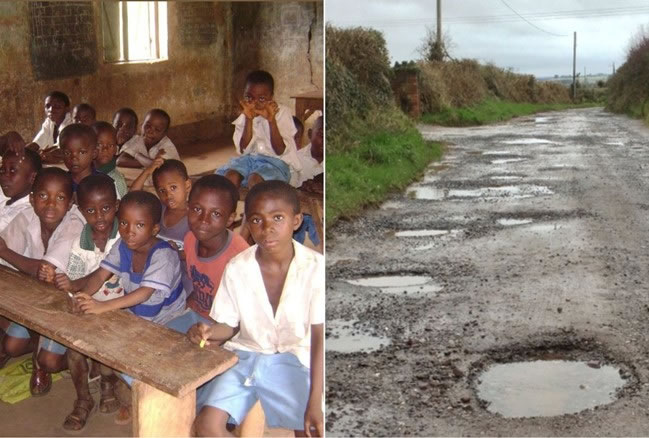

Education vs. infrastructure in catalysing development in Nigeria 18 Jul 2017

Nigerian classroom and road

A few weeks ago, I suggested in a social media post that Nigeria should prioritise education over infrastructure. The knee-jerk reactions I got basically asserted that a choice between education and infrastructure is unnecessary. The two are pressing needs for the country, I was countered. But the impulsive responses merely evaded the debate.

Choice is compelled in public expenditure all the time. Government's development priorities are not only expressed in what it allocates funds to, vis-à-vis what it overlooks; the relative sizes of the allocations do also reveal the policy choices that are made. The debate between education and infrastructure is about which one should attract significantly more fiscal allocation and incentives for private investment.

The debate could be framed in starker terms. Education or infrastructure, which will bring about the more sustainable development in Nigeria? Infrastructures are creations of education and technical knowhow. In the Nigerian environment that is educationally less-developed, built infrastructures are misused and quickly slip into disrepair.

Nigeria's choice

The government of President Muhammadu Buhari does not disguise that its priority is infrastructure development, compared to education. In the 2017 budget, the combined capital expenditure allocated to the Ministry of Power, Works and Housing, and Ministry of Transport, was N791 billion. The capex for Universal Basic Education Commission and the wider Ministry of Education was N142 billion. This was the pattern of capex allocations in 2016.

The huge allocation to infrastructures – mainly roads, rails and power, not specifically tied to the education sector – have ready justification. Nigeria has been in a long and deep economic slump. To reflate the economy, the borrowed conventional wisdom is that the country should invest “massively” in infrastructure. The investments are expected to create jobs and support long-term industrial development. Moreover, the unending epileptic power supply in the country has been a drag on industrial and social development.

However, the choice of infrastructure development over education by Nigeria, and indeed other African countries, is with the encouragement of the multilateral financial institutions and the foreign private investors. Irrespective of the state of disrepair in which education infrastructure has fallen in Africa, and how this would ensure Africa does not become globally competitive in the foreseeable future, the investment theme which global financiers have formulated for the continent is infrastructure investment.

Global investors would rather invest in Nigerian rails, roads, ports and power projects. These kind of projects are often sizeable. Small projects don't meet the appetite of global and big emerging market investors who are in the hunt for huge returns, preferably in a handful of projects. Thus, when, for example, the big road or rail projects are built, the feeder roads to link into them are unavailable.

When this debate pitched Patrick Awuah, founder of Ashesi University, Ghana against Hamad Buamim, Director General, Dubai Chamber of Commerce and Industry, their views were diametrically opposite. “In the long term, the educated community will create the infrastructure it needs and a diverse economy from the materials it has. The stable civil society will attract foreign investment. On the other hand, the foreign-built infrastructure of the … uneducated society is likely to experience a slow collapse, with communities of people doing things much as they did in the past,” Awuah argued.

Buamim countered in the fashion of capitalist authoritarianism: “Infrastructure is what Africa needs now and this is where new investment should be directed. Its development must take precedence over education reform at present because this is where the greatest needs of African people lie.”

The fallacies

A standout fallacy of Nigeria's infrastructure investment is in the fact that the agenda is externally generated. The government has to conceive of projects that can attract the financing interest of global investors. Last year, President Buhari had to return to Nigeria and determine the infrastructure projects his delegation had secured financing for in China. But there are hurdles that must be scaled for external financing to be realised, including macroeconomic stability, impressive GDP growth rate, healthy government's cash flow and benign political risk. On the weakness of nearly all these factors, Nigeria is set to also experience this year the external financing disappointments that thwarted the delivery of the infrastructure projects in the 2016 budget.

As Nigeria apparently did not have the funds to meet its putative infrastructure needs last year, I made the observation that the country also lacked the technology and expertise for the projects. Therefore, the country would not only be paying huge cost of financing for the projects, much of the project funding also would go to foreign countries to acquire expensive equipment and needed expertise.

This is a fundamental difference between our local context and that of the advanced economies or the Gulf States – with huge foreign currency-denominated reserve assets – when hoping to reflate their economies with massive infrastructure investment. Any of the countries would have at least one of the project mix: capital, technology and expertise. Nigeria has none.

It is already evident that it is not the infrastructure investment plans of the federal government that will take the country out of the current recession. It would be the near-total recovery in oil production, following the respite from attacks on oil installations in the Niger Delta. This positive outlook is supported only by oil prices above the 2017 budgetary benchmark of $42.50 per barrel.

Nigeria's longer-term economic performance that is anchored on roads, bridges, rails and power is even questionable. If by the dint of good fortunes the country manages to complete some of the infrastructure projects over the coming years, the facilities will not automatically deliver productivity growth. Other vital inputs for production, including human capital, will prove a limiting factor at a time when public debt would have weighed heavily on fiscal policy.

Education leverage

A sub topic of this debate is whether the inadequacy of the current state of education in Nigeria does not exceed that of infrastructure. However, not only is the crisis-state of our education a threat to productivity and commerce; it is also a threat to life and civil society.

Ten million Nigerian children are not in school. This means the children face a very bleak future of no known effective remediation. With majority of this children in the north, some of them are already cannon fodders for Boko Haram terrorists. A systemic social fracture brews when a large population is denied access to basic education.

The fallen standard of education in Nigeria has been a source of concern for various employers who continue to find graduates from the country's tertiary institutions unemployable. Even as the available public and private universities have limited spaces for those seeking admissions, even so we are finding that students who have completed nine to twelve years of education are barely literate or numerate. If science and technology education and research ever took off in the country, we have since abandoned them.

Prioritising investment in education will help reverse the threat of systemic collapse of the social order. It will do more over the long-run. Developing local expertise through effective and functional education will aid the accumulation of capital in the domestic economy. (In 2013, the US intellectual property holders earned $128 billion.) Local knowhow will drive down the cost of projects, usually heightened by foreign sourcing of experts that dictate project costs.

Giving more priority to education in Nigeria will optimise recurrent expenditure in education. Although education receives relatively low capital expenditure allocation, it actually receives high allocation for recurrent expenditure. In the 2017 budget, education attracted N398 billion, the second-highest allocation for recurrent expenditures. But the value of this humongous allocation is hardly realisable, if not complemented with capital expenditure in education to raise standards of teaching, learning and research.

Education pathway to industrial development

The strongest argument for infrastructure is that it provides the pathway to industrial development. Without the ports, how do we conduct trade? Without the roads, trams and electricity supply, how would we even get to school and power the electrical appliances and equipment for teaching and research?

However persuasive this argument is taken to be, there is an alternative pathway to industrial development for Nigeria. Indeed, for the developed countries, education provided the impetus for industrial and infrastructural development.

There are two policy pronouncements of the Buhari administration that provide pointers to the alternative pathway. In late 2015, the Minister of Science and Technology, Ogbonnaya Onu, said the country would start producing pencils in two years. Nigerians in denial that the country would inevitably enter the technology race at a lower level sneered at him. But Onu's pronouncement, if it translates to concrete programmes with honest actions could serve a model that links the country's quest for technological knowhow and industrial development to the education sector.

But, of course, six months to the kick-off date for this industrial revolution of pencil production in the country, the promise may have dissipated like everything else the Buhari administration has promised and failed to deliver. However, with a ready market, the production of pencils in Nigeria can provide the nudge for further industrial development along the vast education value chain.

The second pronouncement is the school feeding programme. The programme is a key part of the N500 billion social investment plan the administration has touted for two years. The school feeding programme is a symbolic emphasis on achieving learning outcomes by fortifying school children with the nutrition they need.

As described, the school feeding programme was designed to boost local food production. Only locally-produced items would be served. If this programme serves only eggs across the country, we can expect the development of significant additional capacity in the poultry industry, including processing of chicken. And if it entails elaborate meals, we can imagine the number of farm and non-farm jobs it would create, providing a real spark to the long-awaited agriculture revolution. The programme would also help develop the logistics industry. The knowledge derived from serious implementation of the national programme would be useful in the development of the wider agro-processing industry.

But, again, the implementation of the school feeding programme has been underwhelming. Unimplemented in 2016, the programme was transferred to 2017. At mid-year, it remains in a pilot stage in only nine out of the 36 states of the federation and the Federal Capital Territory.

Limit of outsourcing

It is in acquiescence to a future Nigeria that is educationally and technologically uncompetitive, compared to peer nations, that policymakers today have not found the revival of quality education and research a national priority. Arguably, the policymakers, who hardly follow through with policies, found an easy way out by contracting big infrastructure projects to foreign entities. But we definitely cannot build our education system merely by awarding big contracts and outsourcing government's responsibilities to global financiers and project developers as we try to with infrastructures.

Education represents that arduous path to the country's development that we have continued to abandon. It is also an open secret that infrastructure projects in Nigeria are significantly about building cesspits of corruption.

Nigeria has missed the opportunities to simultaneously develop infrastructures and build a first-rate educational system. The petrodollars that would have made that happen have been misappropriated and frittered away through infrastructure boondoggles we have no capacity to maintain. This is unlike some progressive oil producing countries that have healthy savings even after investing simultaneously in infrastructure and education.

A choice is compelled in the Nigerian case now. We can continue to pretend to be building infrastructures without building the people that would use them. Such infrastructures would soon fall into disrepair. But if we invest in education, we will inevitably build the infrastructure we need to harness the innovation and industry of our well-educated population.

Jide Akintunde is Managing Editor, Financial Nigeria. He is also Director, Nigeria Development and Finance Forum.