Efem Nkam Ubi, Acting Director of Research and Studies, Nigerian Institute of International Affairs

Follow Efem Nkam Ubi

![]() @PapaFemo

@PapaFemo

Subjects of Interest

- Economic Development

- Geopolitical Analysis

- International Affairs

- International Trade

Nigeria’s major challenges in 59 years of independence 09 Oct 2019

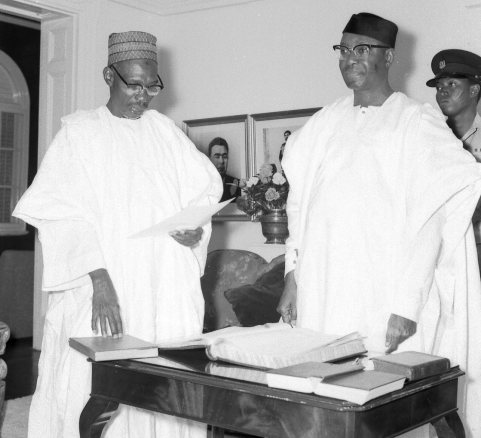

Governor General of Nigeria, Dr. Nnamdi Azikiwe, swearing in Sir Abubakar Tafawa

Balewa as Prime Minister of Nigeria at independence in 1960

On October 1, 2019, Nigeria became 59 years old as an independent state. Do we have a reason to celebrate? And do we have something to showcase with pride, like the Chinese are doing with their economy and the military in celebrating the 70th anniversary of their country’s independence?

The fanfare that greeted Nigeria’s independence in 1960 demonstrated citizens’ hope and aspiration on the prospects of self-governance, at the end of over half a century of the colonisation of the present-day Nigerian territory by Britain. But after 59 years, the hope appears forlorn.

Nigeria’s fundamental challenges as a nation since independence are threefold: leadership, national unity, and economic development. The last two are precipitated by the huge challenge of leadership.

Leadership

The history of governance in post-independence Nigeria cannot be written without highlighting the adverse effect of military incursion into the country’s politics. Indeed, military interventions in the political governance of Nigeria, since the first coup d’état happened in January 1966, accentuated the leadership problems of the country.

Suffice to say that the economic prospects of the country at independence, and in the few years afterwards, were largely eroded by the military regimes.

But, as noted by Prof. Warisu O. Alli of the Department of Political Science, University of Jos, the legacy of the military in Nigeria is mixed. For instance, the military was able to keep the country together after the civil war and took some politically-sensitive decisions. At the same time, military rule was oppressive, autocratic, corrupt and led to the destruction of the political institutions, preventing development of a credible democratic culture in the country.

The military eroded the nation’s federal structure with over-concentration of power at the centre, a phenomenon that has retarded economic growth and development. This structural distortion of the polity has in the last three decades seen strident calls for the restructuring of the country and return to true federalism.

However, the military was not the only problem the country has had with its leadership. The civilian administrations over the years have also displayed leadership ineptitude. Therefore, in his book, “An Image of Africa and the Trouble with Nigeria,” the world-renowned author, Chinua Achebe, opined that the trouble with Nigeria is simply and squarely a failure of leadership. According to him, there is nothing basically wrong with the Nigerian character.

“There is nothing wrong with the Nigerian land or climate or water or air or anything else. The Nigerian problem is the unwillingness or inability of its leaders to rise to the responsibility, to the challenge of personal example which are the hallmarks of true leadership,” he averred.

Nigerian political leaders cannot exonerate themselves from the current travails of socio-economic underdevelopment of the country. Leadership problems and corruption were often, and correctly, cited for making coups in Nigeria. Except that the military administrations, one after the other, perpetuated the same debilities.

It is important that Nigeria’s leaders and citizens realize that across the globe, leadership plays a critical role in statecraft and nations’ development. Clear examples are the “Asian Tigers” and the emerging economies of the 21st century. The leaders of these countries made conscious efforts at engendering economic growth and development for their respective countries. It is important for Nigerian leaders, too, to understand that economic growth and development require political will, commitment and consistency in driving progress.

In other words, for Nigeria to experience sustainable socio-economic development, responsible and credible leaders must emerge to implant the act of good and selfless governance in the country. All we dream about Nigeria as a great nation is realisable only with good leadership.

National Unity

The challenge of national unity has also been intractable in 59 years of the country’s independence. Although this problem existed in colonial Nigeria, it has been festering afterwards.

In my article, “Ethnicity blights democratization and nation-building in Africa,” in Financial Nigeria magazine, January 2019 issue, I highlighted the inclination towards the “ethnos” in Nigerian and broader African politics. The progression of lack of unity and national integration was aptly described by Professor Michael Maduagwu, formerly of the National Institute for Policy and Strategic Studies (NIPSS), Kuru, Jos. He observed that “Our nationalist leaders regionalized their political vision, while their successors personalized them”.

Since the creation of Nigeria, the crisis of ethnicity has been and remains a strong factor that has shaped the Nigerian state, such that beginning from the First Republic, most political parties in Nigeria were founded on ethno-regional configurations. According to Professor Achebe, “nothing in Nigeria’s political history captures her problem of national integration more graphically than the chequered fortune of the word tribe (ethnic) in her vocabulary.” At 59, I will say that the gravity of the Nigerian problem today is the complexity of the rivalries between ethnic, clans and cultural groupings of the country.

Thus, majority of conflicts in today’s Nigeria that have become more vicious are a consequence of ethnicity. Whether or not these conflicts are resource-based, the quest for self-determination, or the clamour for restructuring, etc, point to the ventilation of ethnicity. Also, depending on convenience, religion has also become the twin to ethnicity in undermining the unity of the Nigerian state.

The question is, will the citizens ever begin to see themselves first as Nigerians before their ethnic groups? When are we going to stop asking ourselves on first sight, which ethnic group are you from or what’s your religion? Part of the Nigerian dream should be a Nigeria where anyone could live and work anywhere without the fear of acceptance and integration. But as long as Nigeria is not able to curb its pandering to ethnicity, the country will remain on the brink.

Economic Development

59 years of independence has seen the pauperisation of Nigerians. Since independence, Nigeria has oscillated between the designations of low-income and middle-income country. In the better part of the last decade and a half, Nigeria was a middle-income country. But it has recently slipped into low-income status.

The reason for the lack of economic development is not far-fetched. The economy has remained over-dependent on natural resources – oil exports for revenue and subsistence farming for employment. No adequate consideration was given to industrialisation and advancement in technology.

Nigeria’s economy showed the prospects of a rising country in the last one and half decades, according to various reports, including African Development Bank Group Country Report (2013), which at the time said that Nigeria’s GDP grew at an average rate of 7.01 percent. In comparison to the rest of the world, Nigeria outperformed the emerging markets and developing economies, which grew by 5.75 percent, Sub-Saharan Africa by 5.05 percent, and the global economy by 3.6 percent.

However, Nigeria’s economic growth was driven by crude oil export. Other sectors played minimal role in that regard. The growth hardly denoted sustainable progress. Once the price of oil dwindled in the international market, Nigeria in no time fell into a cyclical economic downturn or recession. This remains the scenario till date.

Even ironically, with the supposed growth, the mass of Nigerian citizens became poorer and inequality intensified. The economic growth did not trickle-down and it will hardly ever do, based on the existing state of the country’s affairs and the transition in the global energy market.

More succinctly, Nigeria’s economy depicts a modest ‘growth without development’. Economic growth has failed to generate or even enable the structural transformation essential for the over-all development of the Nigerian society.

It is necessary to add that the problem of insecurity in Nigeria is also accentuated by its economic woes. It is often said, without development there can’t be peace and neither can there be peace without development. There is no contending formula for political legitimacy in the world today than the ability of government to provide sustained welfare, prosperity, equity, justice, domestic order and security. The absence of these indicators over time could undermine the legitimacy of even democratic governments.

My contention is that Nigeria’s economic stagnation of the last 59 years has been fostered by the corrupt political leadership class that shows more interest in private, group or ethnic gains than in the general wellbeing of the Nigerian citizens. The administration of President Muhammadu Buhari recognises this malady and avers commitment to fighting corruption.

As already noted, the foregoing is not to say that Nigeria is a total failure. Evidence of minimal successes abound. The country has remained one. Progress in the agriculture, banking and telecommunication sectors is undeniable.

But for Nigeria to survive and thrive, the country needs patriotic and nationalistic leaders. Nigeria needs leaders with vision and commitments to implement a sustainable economic growth and development plan for the benefit of all Nigerians.

Latest Blogs By Efem Nkam Ubi

- Why Nigeria's membership of BRICS+ is indispensable

- Military intervention by Ecowas in Niger will cause two major casualties

- Nigeria’s sovereignty and the propaganda against China

- Covid-19 calls for global cooperation not blame war

- Nigeria needs a post-Covid-19 poverty alleviation strategy