Unleashing the potential of Africa’s cotton industry

Summary

Binding arrangements with the private sector present a number of benefits for cotton producers.

Introduction

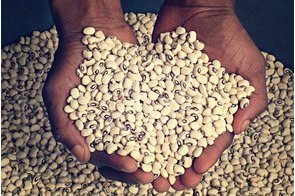

Cotton is one of Africa's most important agricultural commodities. Cotton production is widespread across the continent. 37 of the 54 African countries produce the crop, out of which 30 are exporters. Widely used as a textile raw material, cotton is an important commodity in the world economy. However, the African continent accounts for only about 16 percent of the vast global textiles market, valued at $1.6 trillion in 2015 – a 32.5% increase from 2010. Asia-Pacific accounts for almost 60% of the global textiles market.

African cotton production grew steadily during the colonial era but has failed to transform the economies that now depend on it as a source of valuable foreign exchange. Consequently, the potential for cotton as a vehicle for poverty reduction is no longer certain. Critics point to the growing marginalisation of African cotton smallholders in the international supply chains. Therefore, a reform of Africa's terms of trade is being strongly advocated by cotton producing countries in West Africa, where millions of smallholder farmers depend on the crop for their livelihood.

New private sector partnerships with the cotton industry are beginning to provide much-needed investment for the modernization of the industry through technology adoption. Maximising the potential of the cotton sector, especially through value addition, will depend on the efforts of development partners and national governments to build the capacity of smallholder farmers to reap the financial benefits of a key regional export crop.

Stifling the African cotton industry

Cotton has failed to provide a sustainable means for poverty reduction, especially in West Africa where the top cotton producers also find themselves at the bottom of development indexes. Burkina Faso relies on cotton for 71% of its exports but ranks 181 out of the 187 countries in the UNDP Human Development Index. Benin and Mali, close regional rivals of Burkina Faso in cotton production, rank 165th and 176th, respectively, in the Human Development Index.

Several factors have contributed to the low performance of the cotton sector in the West Africa region. Fluctuations in the world market price of the commodity have dramatic consequence for African farmers. Research shows a direct correlation between declines in cotton prices and an increase in poverty rates by up to 8% in parts of West Africa. The global cotton price has remained relatively flat and shows few signs of returning to the levels of the early 1990s.

Deteriorating terms of trade for African cotton exports are also points of contention at international trade fora such as the World Trade Organization (WTO) where African governments point to the negative impact of hefty Western cotton subsidies, which have kept cotton prices artificially low. This, in turn, has meant low tax revenues from the sector due to the reluctance of African governments to tax the cotton sector as result of limited revenue generated from production. Insufficient investment in the sector also means fewer market opportunities for value addition and employment creation.

In a joint article published back in 2003 in the New York Times, titled “Your Farm Subsidies are Strangling Us,” former Malian president Amadou Toumani Touré and former Burkina Faso president Blaise Compaoré, described the central importance of cotton to national development. They wrote: “Cotton is our ticket into the world market. Its production is crucial to economic development in West and Central Africa, as well as to the livelihoods of millions of people there. . . . This vital economic sector in our countries is seriously threatened by agricultural subsidies granted by rich countries to their cotton producers.”

In “How Europe Underdeveloped Africa,” Walter Rodney highlighted the perpetuation of the unequal trading relationship between Africa and the West when he wrote: “Africa's greatest value to Europe at the beginning of the imperialist era was as a source of raw materials such as palm products, groundnuts, cotton, and rubber. . . . The need for those materials arose out of Europe's expanded economic capacity . . . [and] . . . one of the important factors in that process was the unequal trade with Africa.”

But despite the strong opposition from regional governments, the international and regional civil society groups, the negative impact of North America's cotton subsidies on the African cotton industry still remains.

Niche market opportunities and challenges

The development of niche cotton markets offers brighter prospects for smallholders looking for fairer market returns. For instance, organic cotton has several benefits for African producers because it provides a premium price which is higher than the standard market price for regular cotton. Organic farming is also known to cover a broader farm base which particularly favours women farmers who are typically marginalised.

Initiatives such as the Cotton Made in Africa Initiative, which is run by Aid by Trade Foundation (AbTF), work with smallholder farmers to produce cotton as part of fair trade agreements. Through the initiative, smallholders learn about efficient and environmentally-friendly practices with the help of technical experts. With the aim of improving the living conditions of cotton producers in the region, Cotton Made in Africa has established an international alliance of textile companies which purchase the raw material.

The development of genetically modified (GM) cotton also offers potential advantages to smallholders who are able to use new variants to protect their yields from pests and crop diseases and improve productivity. However, new varieties of cotton come with opportunities and challenges. Meeting new crop standards and classification can come at a cost while putting farmers at risk when harvests fail. The introduction of GM cotton in South Africa was shown to benefit commercial famers but worked against the short-term interests of smallholders who were unable to reap productivity gains.

Research on the introduction of Bt cotton (an enhanced cotton variant) in South Africa produced mixed results due to the dominance of commercial white farmers who were most successful in adopting the technology. Without the right investment in rural infrastructure, enhanced capacity building and widened access to credit, spreading new technology alone will be unable to transform the livelihoods of smallholder farmers who face a number of market constraints.

Partnerships with the private sector can be fruitful for smallholders who lack storage, processing and transport facilities. Out-grower schemes have been identified as solutions to overcome marketing barriers and ensure better income from farming. Olam International, with its headquarters in Singapore, is a multinational agribusiness company that employs over 2 million farmers across the Africa region. It is currently working to develop Africa's cotton sector providing credit, seed and fertiliser while securing a market for farmers following harvests. Focusing mainly in Southern Africa, Olam plans to produce $40 million worth of processed cotton covering 120,000 farmers by 2015.

Binding arrangements with the private sector present a number of benefits for cotton producers who are able to get immediate market access through the emerging out-grower schemes. However, attention should be paid on how cotton farmers can negotiate effectively with the private sector to ensure fair wages and high working standards and practises. Recent allegations of foreign businesses exploiting the rights of farm workers in the region have highlighted the lack of regulation on out-grower schemes and the potential for abuse.

Development partners are supporting cotton farmers to maximise opportunities to boost earnings and improve livelihoods. United Nations Food and Agricultural Organisation is working with smallholders facing limited access to technology and weak agriculture extension services to reverse downward productivity trends. FAO, in partnership with the European Union, aims to intensify cotton production in a way that protects the environment, while improving the competitiveness of the final product and generating income for cotton producers. The project covers Burkina Faso, Mali, Senegal, Tanzania and Zambia.

Conclusion

Cotton farming in Africa represents one of the most important export sectors in the region, providing a means of livelihood for millions of farmers. But the revenue from cotton is continually on the decline, as investment dwindles and global prices remain low. Without a significant turnaround in the terms of trade for Africa's cotton exports, low global prices for cotton will continue to impoverish this vast number of cotton producers who are unable to make a fair market return.

However, the expansion of the agribusiness sector and growth in agriculture investment mean that the cotton sector is well placed to respond to private sector partnerships particularly from the emerging global South which can be instrumental in improving productivity and efficiency levels while boosting income generation. Niche organic and ethnical markets provide a reason for optimism as they provide a profitable alternative to standard market prices while building critical alliances with the international textiles industry.

In the meantime, African cotton exporters, with the support of regional development institutions and national governments, should work towards building the foundation for the development of regional markets. This may offer more lucrative returns in the long run, as the region's textiles industry expands in response to growing consumer demand and expansion of the middle class.

Joan Nimarkoh, Financial Nigeria guest writer, works as a Policy Consultant for the UN FAO. She is a graduate of International Development Studies (MSc) from the school of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, while specialising in African Studies. The article was first published in the July 2015 edition of Financial Nigeria magazine.

Related

-

WTO agreement on fisheries subsidies enters into force

Adopted by consensus at the WTO's 12th Ministerial Conference in June 2022, the agreement's disciplines prohibit subsidies ...

-

A transformed fertilizer market is needed in response to the food crisis in Africa

Natural gas markets are being drained for future winter heating and chemical production, leaving too little for current ...

-

Nothing less than a seed revolution for smallholder farmers

Farmers typically use two types of seed systems — formal and informal.