Cheta Nwanze, Lead Partner, SBM Intelligence

Follow Cheta Nwanze

![]() @Chxta

@Chxta

Subjects of Interest

- Fiscal Policy

- Geopolitical Analysis

- Governance

- Politics

Voter apathy delegitimising Nigeria’s democracy 16 Oct 2020

One of the interesting narratives that came out of the just-concluded governorship elections in Edo State was the backlash against godfatherism. While the defeat of this form of political corruption is an important mark in the political process in the state, there needs to be a discussion about something else that is even more important: voter turnout.

Only 550,000 votes were cast in Edo State on September 19, 2020. Based on the number of Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC)'s Permanent Voter Cards (PVCs) that were collected (1.7 million), the turnout was 32 per cent. Using the standard yardstick of total registered voters in the state (2.2 million), the turnout was much lower at 27.5 per cent. That figure is itself a decline from the reported turnout of 32 per cent in 2016 and nearly 42 per cent in 2012.

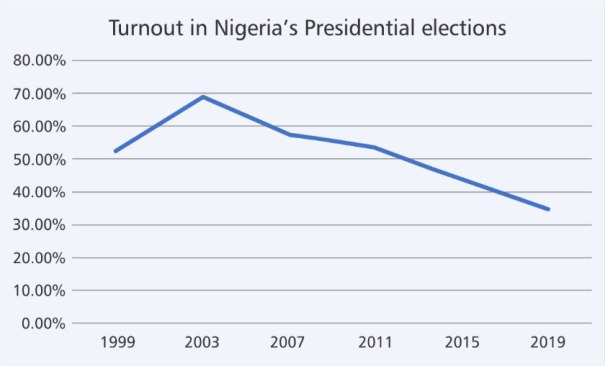

This growing voter apathy is not only a concern for Edo State. There has been a decline in voter turnout nationwide since 2003. In the 2011 presidential elections, voter turnout came in at 54 per cent, down from 58 per cent and 69 per cent in 2007 and 2003, respectively. By 2015, it had fallen to just 44 per cent. In the 2019 presidential elections, it was just 35 per cent. At the time, much was said about the fact that Muhammadu Buhari was re-elected president by a paltry 18.5 per cent of all registered voters.

In effect, less than one in five registered voters backed Buhari in his re-election for a second term. When you consider that the number of registered voters as of last year (82.3 million) is less than half of the entire Nigerian population, it can be safely inferred that just over one in 20 people in our country voted in the current president.

No matter who wins an election, a scenario in which less than 1 in 3 voters show up to the polls to elect their leaders raises fundamental questions about the legitimacy of those leaders and how much the people care about the outcomes of elections. Equally important, it paints a picture of a growing disconnect between the leaders and the citizenry.

Multiple factors are responsible for this growing apathy among the electorate. The spectre of violence is often a major factor that keeps many people away from polls. In fact, many people have lost their lives while trying to vote in elections in Nigeria. A report by my organisation showed that more than 626 people lost their lives in the 2019 general elections in various parts of the country.

The Nigerian political class continues to see winning elections as a ‘do or die’ affair. This provides incentive for political operatives to foment violence or commit acts of electoral fraud, which sometimes lead to violence. In so many cases, law enforcement officials are either unable to prevent violence or arrest perpetrators of violence and electoral fraud. The integrity of election results has also diminished due to rampant rigging, partly leading to the apathetic disposition by the electorate.

INEC's inefficiency is also a cause of low voter turnout. So many people have experienced challenges in registering to vote; some people who register to vote experience various bottlenecks in getting their PVCs without which they cannot exercise their franchise. Moreover, the last three presidential elections, for example, have been marred by postponements due to the electoral body’s inefficiencies.

All these factors that are driving voter apathy are symptoms of a larger problem: the breakdown of the social contract. Around the country, citizens are losing faith in the ability of their elected officials to protect them. From armed Fulani herdsmen clashing with farmers in the Middle Belt and South-Western parts of the country to various bandits, kidnappers and terrorists wreaking havoc across northern Nigeria, it is clear a lot is wrong with the security system of the country. If the state cannot provide security for its citizens, how should that state expect the citizens to participate in elections and give it legitimacy?

Since elections have failed to provide good governance and security; and many government officials are leading by bad examples, citizens are abandoning their civic responsibilities in ever greater numbers. The much-expected ‘dividends of democracy’ have not materialised. Rather, what obtains are worsening socioeconomic conditions, including rising unemployment and poverty.

A 2019 Enough is Enough Nigeria analysis, which compared voter apathy in Nigeria with selected African countries, found that voter engagement was much higher in other countries. In the 2017 Rwandan general election, voter turnout was 98.2 per cent, vis-à-vis a turnout of 79.5 per cent in the 2017 Kenyan presidential election. 59.3 per cent of eligible Gambians participated in the 2016 presidential election. According to the report, two-thirds of Beninese voted in the second round of elections, which handed the current president, Patrice Talon, an unlikely victory over former prime minister, Lionel Zinsou, in 2016. Even with Chad’s 2016 vote, which only served to deepen discontent with Idriss Déby’s three decade-hold on power, 76.1 per cent of eligible Chadians voted.

In the ideological struggle over what political system is the most optimal for delivering economic and human development as well as improved welfare and human rights for the people, democracies have tended to emphasize their ability to mobilise mass participation primarily through elections. Part of the democratic creed is that it is the ideal form of social organisation that ensures that the greatest number of people feel a sense of ownership in the decision-making process by choosing the decision makers.

Hence, what becomes of a democracy – and by extension the policies that emerge from that system – if more than half of the people consistently fail to participate in the process of selecting their decision makers? Many advanced democracies are grappling with ongoing democratic discontent. For many of these countries, rising inequality, structural unemployment and right-wing populism are among factors at the heart of the apathy conversation. In the case of Nigeria, socioeconomic and political headwinds now constitute strong drivers of political discontent.

Many Nigerians are choosing to be model citizens in their personal lives. Policymakers have to commit to finding a way to ensure that casting a vote is not a life and death experience.