Banks are selling shares again

Feature Highlight

What has changed since their public share sales 20 years ago.

20 years ago, the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) launched what remains to date its most impactful programme for the Nigerian banking sector. On 6 July 2004, then-CBN governor, Prof. Charles Soludo, in a historic announcement, said the CBN had decided to raise the minimum capital base of banks in the country from N2 billion to N25 billion, an increase of 1,150%. Regardless of their geographical coverage, type of operation (commercial or investment banking), or even risk appetite, the banks had to meet the new capital requirement by 31 December 2005 to remain in operation under a universal banking model where banks can operate different banking models.

As of the time the policy change was announced, only a handful of the 89 banks in operation had met the extant capital requirement. This made the new capital benchmark quite ambitious. However, the banks didn’t have to meet it individually. Mergers and acquisitions (M&As) were explicitly allowed, making institutional consolidation of the industry one of the more discernible objectives of the capital reform. Indeed, it was somehow decided that there would be no more than 25 banks at the end of what became the first phase of the recapitalisation programme at the end of 2005.

Immediate successes

The programme succeeded in many ways. According to the CBN, N406.4 billion was raised by banks in the capital market, out of which N360 billion was verified and accepted by the apex bank as of 31 December 2005. In effect, the aggregate capital base of the banking sector rose by 96.6%, from approximately $3 billion to $5.9 billion. The desired consolidation of the industry was also achieved, as the number of the banks reduced to 25 as was targeted. From a regulatory perspective at the time, this number was deemed to be more convenient to manage.

With increased capital, the banks were able to fund bigger transactions than they were previously able to do, which was a major objective of the capital reform. The banks were also able to increase consumer lending, which boosted credit penetration in the country. During the share sales, the banks poured billions of naira into the marketing of their public offers. Apart from holding investment roadshows to institutional investors and Nigerians in diaspora, the staff of the banks went door-to-door in Nigeria to canvass for purchase of the shares to many first-time equity investors, thereby popularising both retail and diaspora investments in Nigerian banks.

Without a doubt, the recapitalisation programme laid the foundation for the growth and resilience of the banking industry till date. But the first test of that resilience came during the global financial crisis (GFC) in 2008. While most of the banks passed the test, a few of them dangerously failed it. Nigeria was majorly impacted by the aftershock of the crisis, through a spectacular collapse of oil prices from a peak of $140.36 per barrel (pb) in July 2008 to $45.17 bp three months later in October. As a result of the crisis, $44.47 billion was wiped off Nigeria’s gross domestic product (GDP), which fell from $339.48 billion in 2008, to $295.01 billion in 2009. As would be expected from this vulnerability of the economy to external shock, through high dependency on the proceeds of crude oil exports, the banks took a big hit as they were heavily involved in lending to the oil industry. For instance, the nonperforming loans (NPLs) in the sector rose from 6% to 28% of total loans in December 2009, according to IMF. Without the capital boost four years earlier, however, it is arguable that the GFC would have had more devastating effects on the banking industry and on the economy.

Programmed failure

Nevertheless, the crisis in the domestic banking industry had some of its roots in the capital reform that preceded it. Although the sector’s total capitalisation did increase, much of the increase was driven by bubbles in the prices of the banking stocks. Many banks inflated their share prices by lending to individual and corporate entities (so-called margin loans) to buy their shares. This meant the banks were not as well capitalised as they had presented themselves to be.

Moreover, investigation by the CBN in 2009 showed that the banks were being fraudulently mismanaged by some founders and management, apart from poor risk management that was headlined by the high concentration of loans in the oil and gas sector without hedging the risk. A trifecta of economic bad news, high NPL ratio, and the stock market bubbles saw a spectacular crash in the prices of bank stocks. While the All-Share Index of the Nigerian Stock Exchange fell from 63,016.00 points in March 2008 to 20,827.17 points in December 2009, the CBN’s banking sector rebased index fell from 100 points to 37.64 points in the same period. This highlights the fact that banking stocks were more impacted during the crisis. According to the IMF, 10 banks were particularly hit because of their large exposure to equity-related loans.

Why banks are raising capital now

There are many reasons the banks are raising fresh capital now. According to the CBN, the banks need to raise additional capital to counter the current and emerging macroeconomic challenges, address global and domestic uncertainties, and support the Nigerian government’s vision of creating a $1 trillion economy by 2030. The new capital raise strategy to bolster the country’s economic growth aligns with a key agenda of Godwin Emefiele, as contained in his acceptance speech when he was reappointed as CBN governor in June 2019. But while the recapitalisation agenda was muted during his tenure, the current apex bank governor, Olayemi Cardoso, has more determinedly reintroduced it.

Stripped of economics’ technical lingo, a clearer reason for the current recapitalisation of the banks is that the dollar value of their regulatory capital has considerably declined due to the prevailing naira exchange rate. At the end of 2005, the capital benchmark of N25 billion for the banks was equivalent to $193.7 million. But on 28 March 2024 when the CBN issued its circular announcing the recapitalisation programme, the previous capital benchmark was equivalent to $18.7 million, based on the official exchange rate of the naira on that date.

The depreciation of the naira by over 931.5% in approximately 18 years indicates a yearly average depreciation of the currency by 51.7%. This hints at the failure of the CBN to maintain financial stability, even as the apex bank and the government failed to spur economic productivity and diversification of the external earnings beyond the proceeds of oil and gas exports. The declining naira value, external shocks from oil prices, and the Covid-19 pandemic saw the country’s GDP drop from its $574.18 billion peak in 2014 to $362.81 billion in 2023. An estimate by the IMF sees the value dropping further to $253 billion by the end of 2024, with Nigeria losing its ranking as the largest economy in Africa to becoming fourth-placed in the continent.

Bolstering the capital base of banks is helpful to make them more resilient to crisis, contribute to economic growth and job creation (if the capital is deployed to productive activities), as well as improve their profitability as they are able to increase their lending and take advantage of investment opportunities. As a result, the banks have, on their own, been increasing their capital since the mandatory recapitalisation programme of 20 years ago ended. But their capital needs continue to mount in the face of economic shocks and mismanagement by the fiscal and monetary authorities.

New capital requirements

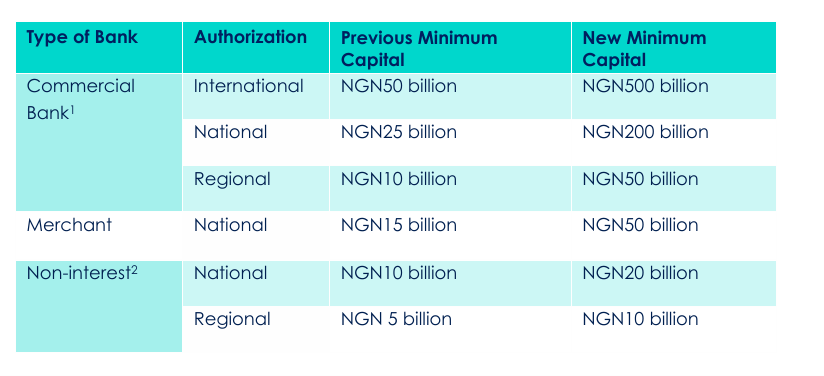

Unlike in 2004, the new capital requirements of the banks are stratified. Commercial banks with international authorisation are to increase their minimum capital from N50 billion to N500 billion. The table below provides the breakdown of the stratification of the changes in the capital requirements across commercial banks (with international, national, and regional authorisations), merchant banks, and non-interest banks.

Analysts estimate that an aggregate of over N4 trillion in fresh capital injection is required by the banks to meet the new capital benchmarks. But this assumes that all the existing 24 banks at the time the circular was issued would want to individually comply. However, the CBN allows for further consolidation of the banks through M&As. In which case, only a fraction of the amount would be raised if some banks decide to combine their businesses through approved schemes of business combination for the banking sector. A further reduction in the projected aggregate amount to be raised could occur if banks decide to downgrade their licence authorisations, like commercial banks with national authorisation downgrading to regional licence.

Prospects of the new share offers

The CBN has given the banks a period of two years (April 2024 – March 2026) to comply with its new capital requirements. Pursuant to this, some of the banks have quickly launched new public offers of shares and rights issues. Fidelity Bank, Access Bank, Zenith Bank, GT Bank, and FCMB have come to the market. Some of the offers had concluded as of the time of writing, but it was unclear how successful they were.

These early movers indicate that they would be trying to meet the capital requirement for their tier through organic capital growth. It could also mean that they want to be at a vantage position to acquire smaller banks or strengthen their position in likely merger negotiations. The outcomes of these early moves would provide insights into the appetite for banking stocks in the primary market. The appetency of investors, especially retail investors, is expected to be heavily impacted by the ongoing macroeconomic challenges and other issues adversely impacting the business and investment environment.

The new capital raise is taking place at a contrasting time compared to 2004. Then, the economy was growing at a much faster speed and the country was coming out of the doldrums of the last decades caused by military autocratic rule and economic mismanagement. Now, the economy has been stuck in a rut, where average GDP per capita growth has been negative over the last decade. Public debt service obligation and unemployment, inflation, and poverty rates were on a positive trend 20 years ago compared with the entrenchment of negative outlook of the indicators since the recent past years. The political economy in the mid-2000s was appealing as the country had just ended decades of military rule, efforts at rebuilding public institutions (including those facing the market) were taking place, and rising oil prices inspired positive outlook. The opposite is the case today with widespread disillusionment caused by the failing of the country’s democracy, capitulation of institutions to vicious political control, and massive oil theft and lack of investment – eviscerating the Nigerian oil economy.

Public sentiments for the offers are also going to be impacted by past negative experiences of investors in the shares of the banks. One of Nigeria’s urbane pastors, Matthew Ashimolowo, in a recent interview on Arise Television narrated his bad experiences. He seemingly scandalised bank founders and directors ‘whose fortunes improve as those of investors in the stocks of their banks plummet.’ Anecdotal evidence suggests Ashimolowo’s accusation hints at something truly tragic.

Assuring changes

While investors are right to be wary, it is important to note that much has changed in the regulatory landscape that would prevent the scandalous collapse of the global and Nigerian stock markets like in 2008/2009. Broadly, changes in capital rules have tended to discourage excessive risk-taking. Similarly, rules on proprietary trading would have financial institutions using their capital, rather than client funds, to conduct financial transactions. These and other stringent rules are underpinned by corporate governance codes, which have bolstered the boards of financial institutions, including through the mandatory appointment of independent directors.

In Nigeria, attempts have been made to reduce the influence of the founders, most of whom can no longer serve as CEOs of their banks after serving out their maximum tenure of 10 years. This, at least, ensures fresh talent and skills are brought to the executive leadership of the banks.

The scope for manipulating the prices of stocks before a public offering or rights issue has been reduced through the rules on margin lending. Banks can no longer lend money for the purchase of their own stocks. As such, they can no longer create a phoney bullish market of their equities. The data landscape has also evolved since 2008, enabling prospective investors to gain more insights into the stocks that are offered for sale. Scrupulous individual and institutional investors can leverage historical data on the trends in the prices of the equities to determine if there has been a suspicious spike in their valuations.

However, none of these is foolproof against overpricing of equities, neither is their collective whole. The best protection against unethical behaviour is the education of the investors in selecting the stocks they invest in, and the moderation of their greed. Unfortunately, the performance of stocks is impacted by political and macroeconomic mismanagement, of the proportions that have been pervasive in Nigeria, especially in the last decade.

Necessary precautions

It is safer for banks to continue to grow organically. This would enable them to maintain their culture. The superiority of culture over strategy has been well stated by the assertion that the former eats the latter for lunch. Similarly, banks should ideally determine when they want to explore opportunities for business combination. When many banks are forced to substantially recapitalise at the same time, a race to the bottom may be inadvertently unleashed as regulators become self-interested, wanting to justify their capital reform by its success. This may have informed the deficiency in the supervision of the banks during and after the 2004 recapitalisation programme until a change in the leadership of the CBN in 2009 unearthed the rot in the banking industry. Indeed, 24 banks were thought to have met the capital requirement but a 25th bank had to be admitted in keeping up with the predetermined number of institutions post-recapitalisation.

This time, the CBN is leaning heavily on the banks to address macroeconomic challenges they are not primarily responsible for, although they are impacted by them. The ambition of growing the economy to $1 trillion is not new. Previous administrations pursued substantial Nigerian economic expansion, including under the Vision 20 2020. But as reality has shown, much more than stated ambition is required to attain the lofty economic height. The Nigerian economy is substantially smaller today than it was in 2010. The factors that eroded the GDP did not spare bank capital either. This is why the CBN should focus a lot more on fostering macroeconomic stability and effective regulation of the banks.

The apex bank should also be circumspect in instigating M&As during the current exercise to preserve jobs and not further stoke unemployment. Nigeria is mostly said to be underbanked from the perspective of the number of people who do not have (or have inadequate) access to financial services. But with only 36 deposit money banks currently licenced in the country, Nigeria could be institutionally underbanked. South Africa, which has less than one third of the Nigerian population, and until recently smaller than Nigeria’s economy, had 30 registered banks as of 2023, while Egypt had 37, and Malaysia had 53.

The CBN should also ensure that its recapitalisation programme does not provide conduits for money laundering, which could taint the country’s banking sector and the economy. Equally important is substantial local ownership of bank equity capital for the retention of wealth generated by the banks in the domestic economy.

It is early days in the implementation of the new bank recapitalisation programme. But throughout its duration (which should be extended beyond the current deadline if necessary), the CBN and the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) should ensure consumer/investor protection.

Jide Akintunde is Managing Editor, Financial Nigeria publications. He is also Director, Nigeria Development and Finance (NDFF).

Other Features

-

Can you earn consistently on Pocket Option? Myths vs. Facts breakdown

We decided to dispel some myths, and look squarely at the facts, based on trading principles and realistic ...

-

How much is a $100 Steam Gift Card in naira today?

2026 Complete Guide to Steam Card Rates, Best Platforms, and How to Sell Safely in Nigeria.

-

Trade-barrier analytics and their impact on Nigeria’s supply ...

Nigeria’s consumer economy is structurally exposed to global supply chain shocks due to deep import dependence ...

-

A short note on assessing market-creating opportunities

We have researched and determined a practical set of factors that funders can analyse when assessing market-creating ...

-

Rethinking inequality: What if it’s a feature, not a bug?

When the higher levels of a hierarchy enable the flourishing of the lower levels, prosperity expands from the roots ...

-

Are we in a financial bubble?

There are at least four ways to determine when a bubble is building in financial markets.

-

Powering financial inclusion across Africa with real-time digital ...

Nigeria is a leader in real-time digital payments, not only in Africa but globally also.

-

Analysis of NERC draft Net Billing Regulations 2025

The draft regulation represents a significant step towards integrating renewable energy at the distribution level of ...

-

The need for safeguards in using chatbots in education and healthcare

Without deliberate efforts the generative AI race could destabilise the very sectors it seeks to transform.

Most Popular News

- NDIC pledges support towards financial system stability

- Artificial intelligence can help to reduce youth unemployment in Africa – ...

- Afreximbank backs Elumelu’s Heirs Energies with $750-million facility

- AfDB and Nedbank Group sign funding partnership for housing and trade

- GlobalData identifies major market trends for 2026

- Lagride secures $100 million facility from UBA