Interview: Mary Robinson

Summary

Climate change isn’t gender-neutral; women bear the brunt of its effects.

In December, in Say More, Project Syndicate spoke with Mary Robinson, former President of Ireland, former UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, and current Chair of The Elders. The interview is republished here under the contents agreement between Financial Nigeria and Project Syndicate.

Project Syndicate (PS): In April, you and Daya Reddy noted that the COVID-19 pandemic “has shown that governments can act swiftly and resolutely in a crisis, and that people are ready to change their behaviour for the good of humanity,” and you called for the same urgency to be adopted vis-à-vis climate change. But, eight months later, “pandemic fatigue” has set in, weakening compliance with public-health restrictions. What does this imply about effective climate solutions?

Mary Robinson (MR): While the World Health Organization and others have used the term “pandemic fatigue,” I urge caution in applying this label. We must not conflate the anxiety associated with lockdowns – often linked to economic concerns – with an unwillingness to adhere to public-health guidance.

Millions of people around the world are facing significant adversity. Governments must provide adequate financial and social protection, so that the poor and marginalized do not feel they must choose between protecting their health and providing for their families. And they must address the deeper social inequalities that the pandemic has exacerbated.

When we consider climate change, what is sometimes construed as “fatigue” may actually be the high psychological and even physical toll of recognizing the seriousness of the threat we face. This is why I have such admiration for the young people, indigenous activists, and other dogged lone voices who have called for climate action for decades.

Today, the climate movement has momentum. We also have frameworks, including the Paris climate agreement and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, which comprises the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). And we have convening moments, like the Conference of the Parties (COP) under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. We must use these mechanisms to hold government leaders, businesses, and industry accountable. More broadly, we must view the COVID-19 pandemic as an opportunity to build a system that rewards social responsibility, does not tolerate short-sightedness or greed, accepts science, recognizes nature’s limits, and leaves no one behind.

PS: You and Reddy highlighted “the need to put social justice at the heart of our climate response” – an imperative you and Desmond Tutu also emphasized in 2011. To what extent do existing frameworks reflect this principle? Which programmes, policies, or approaches are needed to advance this imperative?

MR: We have come a long way. When I first started working on the concept of “climate justice,” it was perceived as a niche issue. It is now a widely accepted principle, and both governments and businesses have increasingly been aligning their plans with the Paris climate agreement and the SDGs.

But their efforts do not go far enough. If we are to limit global warming to the Paris accord’s target of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels, governments must commit to – and fulfil – far more ambitious Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs). We also need to see concrete plans for a just transition to a world powered by clean energy. All climate action must fully respect human rights.

We have the frameworks; what we need now is sufficient drive and determination from the very top. We need leaders to recognize that multilateralism is the only viable path to a green, sustainable, and equitable future for all – and act accordingly.

PS: As you, Amina J. Mohammed, and Christiana Figueres noted in 2015, women are “among those most vulnerable to the impacts of unsustainable practices and climate change.” But, given their position “at the heart of the household’s nexus of water, food, and energy,” they also have valuable insights into “the challenges and potential solutions in these areas,” and should thus be “at the forefront of decision-making.” Five years on, are efforts to engage women in decision-making on sustainable development heartening or disappointing? What changes are most crucial to boost female engagement?

MR: Climate change isn’t gender-neutral; women bear the brunt of its effects. But it is not only their vulnerability that makes their insights invaluable. Women are frequently at the vanguard of efforts to protect our environment. Often, they are early adopters of new agricultural techniques and become green-energy entrepreneurs. They are also first responders in crises, and decision-makers in the home.

I was on a panel with the documentary filmmaker Megha Agrawal Sood earlier this year, and I was struck by her call for “stories as diverse as the ecosystem we seek to save.” She was highlighting that, until now, the climate-change narrative has been dominated by white male voices from the Global North. The same is true of international politics and diplomacy; we need far greater diversity in decision-making at every level.

At COP25 in December 2019, an ambitious new five-year plan for gender-responsive climate action was adopted. The so-called Gender Action Plan was a significant accomplishment, which will strengthen the consideration of gender and boost women’s participation in this area. But we need more women in leadership positions across the board: at the ministerial level, at the ambassadorial and diplomatic level, as civil servants, and at the grassroots level. If we are to stand any chance of successfully tackling the climate crisis, we cannot afford to treat diversity as a “bonus” – a desirable but non-essential piece of the puzzle. We must recognize it for what it is: a prerequisite to progress. Women are already engaged in the issues; we need to enable them to help create the solutions.

PS: Last November, you, Mo Ibrahim, and Kevin Watkins – along with several co-signatories – wrote that with “hard-won progress on reducing extreme poverty and malnutrition, combating child mortality, and extending educational opportunity” at risk, “we need a trading system that works for the poor.” Do you think the COVID-19 crisis, which has spurred many countries to rethink their trading practices, will accelerate or impede the needed reforms?

MR: One of the most concerning aspects of the crisis of multilateralism of recent years has been the near-paralysis of the World Trade Organization – partly a result of the obstructionist and isolationist attitude of outgoing US President Donald Trump’s administration. WTO member states’ failure to agree on a new director-general is the latest – and most egregious – example of this dysfunction. If we are to overcome the health and economic challenges we face and secure a recovery that leaves no one behind, we will need strong leadership and collective action. This must include a concerted effort to minimize disruptions to the multilateral trading system.

The COVID-19 crisis has shone a spotlight on the need for multilateral rules. Under new leadership, the WTO could also play a crucial role in reframing global trade policies in line with the priorities of decarbonizing growth, protecting biodiversity, and cutting pollution.

By the way . . .

PS: Two years ago, in an interview with the Guardian, you lamented that “the United States is not only not giving leadership, but is being disruptive of multilateralism and is encouraging populism in other countries.” The impending change of leadership in the US promises to change that. But will it have the same impact today as it would have been four years ago? With regard to climate change, in particular, how should Joe Biden’s administration exercise US leadership?

MR: President-elect Joe Biden cannot recover the time that has been squandered by the outgoing administration. But we must now look forward, not backward. Every action taken to reduce baked-in global warming matters, and there is much Biden can do.

Already, Biden has committed to rejoining the Paris climate agreement on his first day in office. This is a symbolic move, but an important one. He has also vowed to restore the environmental protections Trump dismantled. Though polarization, together with a lack of strong majority support in the Senate, will limit his options, he can use executive orders to reverse many of Trump’s climate policies.

In the short term, Biden must also stand firm on his commitment to foster green jobs and advance decarbonization as part of the pandemic recovery. More fundamentally, he must seek to close the gap between the level of climate ambition expected globally and his administration’s ability to deliver it. I very much look forward to the US re-establishing itself as a global leader on climate.

PS: Your 2018 book, Climate Justice: Hope, Resilience, and the Fight for a Sustainable Future, highlights stories of strength, ingenuity, and progress in the battle against climate change. What real-world effects do such stories have?

MR: When trying to galvanize support for climate action, a formidable fossil-fuel lobby is hardly the only challenge we must overcome. We also need to find a way to rise above the noise, the distractions from – and indifference to – injustice in daily life. While the majority of people now recognize the realities of the climate crisis, it is easy to feel immobilized by the scale of the problem. Stories help to counter this paralysis, energizing people to support changes to destructive policies or to hold their governments accountable.

The individuals featured in my book show that there is not a one-size-fits-all approach to tackling the climate challenge. We need all of humanity’s skills, perspectives, resourcefulness, and ingenuity.

Consider Sharon Hanshaw’s story. Sharon lived an ordinary life as a hair-salon owner until Hurricane Katrina decimated her salon – along with many other homes and businesses – in her neighbourhood in Mississippi. After the storm, federal relief programmes utterly failed her and other marginalized women. In response to this injustice, she established Coastal Women for Change, an organization that advances women’s empowerment and community development. She went on to become a local, then national, and eventually global voice for climate justice. Sharon did not set out to be a climate activist. But through her honest storytelling, she has made a huge difference.

PS: Your podcast, Mothers of Invention!, which you host with the comedian and writer Maeve Higgins, combines often-mordant realism, thoughtful optimism, and wit. What have you learned from finding humour in serious topics? What impact would you say the podcast – and its droll approach – has had in advancing “feminist climate-change solutions”?

MR: I think people have responded so well to Mothers of Invention! because, while the subject matter is serious, the podcast is light-hearted in tone and hopeful in its outlook. So, instead of feeling paralyzed or weighed down by the climate crisis, listeners can hear about constructive solutions in a positive, friendly way. And it is always good to laugh!

It is no longer just Maeve and me hosting, either. In the latest series, the talented series producer Thimali Kodikara joins us more often. When I am recording the podcast, I feel as though I am gathering together with friends. I hope listeners get a similar feeling.

The podcast looks at the intersectionality of issues. Far from focusing exclusively on climate science, we explore how the climate crisis relates to issues like colonialism, racism, poverty, migration, and social justice. We are not prescriptive; through the stories we feature, we try to show that there are many different ways individuals can contribute.

In 2020, one of our priorities has been highlighting the feminist principles at the core of the show. We have been encouraging our audience – and ourselves – to invest time in self-care, to pursue our climate goals in an inclusive and caring way, and to internalize the historical lessons necessary to create a fairer and brighter future for all.

PS: Speaking of effective messaging, you’ve praised the young Swedish climate activist Greta Thunberg for “humanizing” the climate issue, noting that her 2019 speech at the United Nations Climate Action Summit moved you to tears. As someone who has been working in this area for a long time, what advice would you offer to young activists like Thunberg as they press leaders to translate their message into policy?

MR: I wouldn’t offer any advice! These bold young activists’ main message has been an unwavering plea for leaders to listen to the science and to fulfill the commitments they made in Paris in 2015. And, with that message, they have drastically raised awareness of the climate crisis. My fellow Elders and I stand in solidarity with them.

If I were to offer advice to anyone, it would not be to Thunberg or other young activists, but to world leaders, governments, and businesses. My recommendations would be simple: listen to the young people, listen to the science, and take urgent action.

Copyright: Project Syndicate

Related

-

Germany to provide $33mn to hedge climate investments in Africa

The Long-Term Foreign Exchange Risk Management instrument was created to address currency and interest rate risk.

-

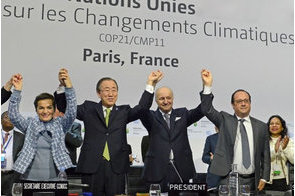

Power Africa launches new initiatives at COP21 in Paris

Scaling up access to cleaner electricity helps mitigate climate change and enhances resilience to climate shocks.

-

Paris climate agreement creates $23 trillion investment opportunities in emerging markets – IFC

SSA represents a $783 million opportunity – particularly for clean energy in Cote d’Ivoire, Kenya, Nigeria, and ...