Nigerian mixed economy

Feature Highlight

How the country’s mixed economic system works and doesn’t work.

Summary: Nigerian industries and markets work fairly well where the government is the regulator, and the private sector is the operator. But it is a rule of thumb that when the government serves as a regulator and operator in any industry, including the petroleum industry, it renders both functions ineffectual.

Like most countries of the world now do, Nigeria operates a mixed economic system. A mixed economic system combines the attributes of the command economic system and market economic system. In a command economic system, a central authority, which is usually the government, controls much of the economic structure. But in a market economic system, governmental control is very limited. In theory, the market regulates itself in a market economic system, through the interplay of demand and supply, which determines prices.

In a delicate balancing act, the mixed system tries to optimise the advantages of the two systems it combines their characteristics and minimise their disadvantages. The advantages of the command economic system include its potential to foster full employment, control inflation, and direct investment towards specific sectors of high economic or social impact. Its drawbacks include stifling innovation and limiting consumer choice. As for the market economic system, its merits are increased efficiency, productivity, and innovation. It has also been credited with fostering fair competition. But its demerits include income inequality, exploitation, and market failures.

In a continuing process of policy and market reform, which aims to optimise the merits of the two systems and limit their demerits, countries have achieved varied levels of success in implementing the mixed economic system. In the mixed system, most industries are operated by the private sector, and public services are run by the government, which also exercises regulatory control of the entire market.

Nigeria’s mixed economy is underpinned by a large private sector and the institutional regulation of industries and markets. Foreign multinational companies used to dominate the large corporate segment of the Nigerian private sector with the presence of global energy giants such as the European Shell, Total, and Eni, and American Mobil and Chevron. British manufacturers and trading companies like Cadbury and UAC also had dominant presence in the Nigerian market. In the last two decades, however, big indigenous companies, such as Dangote Industries and BUA Group, have emerged with large banking franchises including Zenith Bank, Access Bank, and Guaranty Trust Bank, amongst others. On 18 March 2025, the NGX-30 sub-index of the Nigeria Exchange Limited (the country’s stock exchange), which comprises the 30 largest equities by market capitalisation on the exchange, accounted for 90.4 percent of the total equity capitalisation of the exchange.

However, there were 39.65 million micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) in Nigeria in 2020, according to a survey by the Small and Medium Enterprises Development Agency of Nigeria (SMEDAN). They accounted for approximately 80 percent of employment and 40 percent of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP). Data from Statista shows private investment as a percentage of Nigeria’s GDP reached 17.2 percent in 2023, which is comparable to the 17.8 percent in the United States and 19.3 percent average in the European Union (2022 data).

In terms of regulation, virtually all sectors of the Nigerian economy are regulated by the government through its regulatory agencies. The National Agency for Food and Drug Administration and Control (NAFDAC) exercises regulatory control across many industries that produce and distribute or sell food and beverages, drugs, medical devices, chemicals, cosmetics, detergents, and others. The Nigerian financial services sector is one of the most regulated in the world. For instance, the banking regulators include the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN), Nigeria Deposit Insurance Corporation (NDIC), and Financial Reporting Council of Nigeria (FRC). As publicly-listed companies and/or operators in the capital market, the banks are also regulated by the Nigeria Exchange Group and/or Securities and Exchange Commission. Many of the functions of the financial services sector regulators overlap. But while the regulatory functions tend to be fragmented, the regulators often work cooperatively.

The heavy regulation of the banks, for instance, serves as a safeguard for depositors’ fund, which helps in maintaining financial stability in the economy. But there are concerns around the curtailment of innovation and the high-cost of regulatory compliance. This notwithstanding, the continuing modernisation of market regulation in Nigeria has contributed immensely to the country’s economic and market stability and growth.

One of the reasons for the successes of regulation in the financial services sector is the separation of the role of government as a regulator from that of the private sector as operators. Government’s majority ownership in the financial services sectors is largely restricted to the Development Finance Institutions (DFIs), which are specially mandated to intervene in industries and industry segments that are considered high-risk by private sector financial institutions. Indeed, some of the DFIs, including Bank of Industry and Development Bank of Nigeria, deploy their financing interventions through the private sector banks.

As an example from other sectors, after the collapse of the Nigeria Airways – the state-owned national carrier) – in the early 2000s, the federal government has focused more on the regulation of civil aviation in the country. The industry is now dominated by private investors.

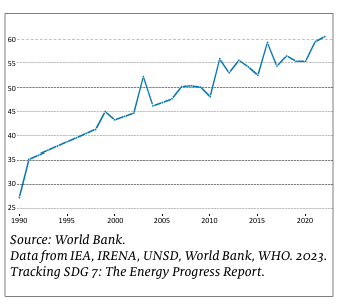

Nigerian markets don’t tend to function well where the government plays as a regulator and operator – usually as a monopoly. For decades, the government was both the monopolist and regulator in the electricity and telecommunication markets. It never performed either of the functions competently. Service coverage and quality of service in both markets were poor. While access to electricity supply in Nigeria has remained low at just above 60 percent, with supply largely still epileptic, the peaks of access were recorded after the dismantling of the government’s monopoly in power generation and distribution in 2013, data from the World Bank shows.

Figure 1: Access to electricity (% of population) - Nigeria

The transformation in the telecoms sector is even more dramatic. Before 2001, the country relied primarily on landlines, with a total of 400,000 lines serving a population of approximately 120 million. But that year, the government signalled its intention to play in that industry more as an effective regulator when the Nigerian Communications Commission (NCC) sold GSM spectrum licences to private investors. While the public monopoly at that time, Nigerian Telecommunications Limited – or NITEL for short – is now defunct, there were over 224 million active telephone lines in the country at the end of 2023, offering modern voice and data services.

However, the government has not effectively applied these lessons in the oil & gas industry, which has remained critical not only to the economy but also for government’s revenue. Nevertheless, it is a rule of thumb that when the government serves as a regulator and operator in any industry, including the petroleum industry, it renders both functions ineffectual. The national economic security consideration behind the fusion of the roles in government is often overtaken by vested interest that undermines it.

But following the enactment of the Petroleum Industry Act (PIA) 2021, the government incorporated NNPC Limited (NNPCL) as a limited liability company under the Companies and Allied Matters Act, paving the way for its commercialisation and potential future privatisation. The legislation also created the Nigerian Upstream Petroleum Regulatory Commission (NUPRC) and Nigerian Midstream and Downstream Petroleum Regulatory Authority (NMDPRA) to regulate the value chains of the industry. But until a majority equity stake of NNPCL, the national oil company (NOC), is sold to private investors, the government will remain a regulator and a major operator in the energy sector. In this scenario, the more things change in the sector, the more they are likely to remain the same, if not worse. The now-defunct Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation (NNPC), the forerunner of NNPCL, had underperformed for decades due to underinvestment in its upstream activities of oil and gas exploration and production. And in the midstream and downstream sectors, NNPC had relied on the importation of refined petroleum products to supply the domestic market for decades despite owning four refineries. The country also witnessed regular shortage of petrol supply as NNPC’s monopoly as a refiner orchestrated a market failure in the petroleum industry. This legacy has persisted, making the recent legal reform to yield just name change and not culture change at NNPCL, more than three years after the PIA came into effect.

Since the Dangote Petroleum Refinery and Petrochemicals Limited (Dangote Refinery) started its production of petrol in September 2024, there have been new insights about the malfunctioning of the Nigerian mixed economic system. In the past, government’s self-regulation of industries where it operated as a monopoly witnessed the demise of the public enterprises and market failures. But now, a major private business has sprung up in an industry where the government has been a regulator and a monopolistic operator, and Dangote Refinery appears imperilled because of this situation.

Dangote Refinery, owned by one of Africa’s richest entrepreneurs, is a challenge to the government’s dual role in the oil & gas industry. The refinery is reputed to be the single largest local investment in Nigeria. The integrated facility cost over $20 billion to build and can process 650,000 barrels of crude oil per day, which can more than meet Nigeria’s domestic petrol demand. This refining capacity exceeds the total capacity of the four NNPCL’s refineries of 445,000 barrels per stream day – although none of them is independently confirmed to be currently working after years of their turnaround maintenance. The Dangote Refinery is a challenge to NNPCL – either as a refiner or importer of petroleum products – and, therefore, the government: its owner.

During the building phase of the private refinery, the government rationalised its support for the company. The rationales for the preferential allocation of foreign exchange to the refinery by the CBN were that it would help the country to save the billions of dollars expended on petrol importation annually, reduce price volatility of the product in the local market, and ensure regular supply – which are some of the classical goals of regulation. But apart from these economic benefits, the government also addressed the potential financial loss by NNPCL in the era of the operation of Dangote Refinery by signing a deal to acquire 20 percent equity in the private refinery. Despite public concerns that the equity sale close to the operational launch of the refinery might have been involuntary, public information suggests that Aliko Dangote was a willing seller of the equity stake in his eponymous refinery. But he would later disclose: "NNPC no longer owns a 20% stake in the Dangote refinery. They were (meant) to pay their balance in June but have yet to fulfil the obligations. Now, they only own a 7.2% stake in the refinery." NNPCL responded by indicating it has changed its business strategy since making down payment for shares in Dangote refinery.

Despite the economic reasons for the government’s support for Dangote Refinery, the refiner has been operating in a hostile regulatory environment. First, Farouk Ahmed, CEO of NMDPRA, claimed that the quality of diesel produced in the country, including at Dangote Refinery, was inferior to the quality of the imported substitute. Later, the CEO of NUPRC, Gbenga Komolafe, asserted the willing-buyer-willing-seller provision of the PIA while countering as “erroneous” Dangote’s allegation that the international oil companies (IOCs) were frustrating his efforts to source crude oil feedstock for his refinery locally.

Dangote got a reprieve with regard to local access to feedstock. The government provided him the naira-for crude programme, under which NNPCL supplied crude oil to the refinery in the local currency. But according to the NOC, the deal has automatically entered its sunset in March 2025 after the expiration of its six-month duration. While the deal lasted, competition in the petrol retailing sector did not make an appreciable economic or market sense. NNPCL and independent marketers massively imported petrol into the country despite the product’s inventory at Dangote Refinery. Despite selling at marginally lower prices, the refinery only managed to have four retailers to seller its petrol. In attempts to gain local market share, the refinery dropped its prices a couple of times. These incidents dovetailed into the suspension of the naira-for-crude deal. Again, the government is trying to mediate a solution on a likely renewal of the deal.

If Dangote Refinery has to rely on sourcing crude oil in dollars, either from the local or external market, it would lead to higher prices for the consumers. It would also erode stability of the exchange rate as demand pressure would build up again from downstream petroleum sector activities in the FX market. One explanation for the seeming lack of interest by the industry regulators to forestall crisis in the market and promote a pricing regime that favours the consumer could be that they are functioning at cross purposes with the government. But did they have the independence to do so, and why has the government not demanded their proper functioning? The explanation becomes implausible, giving away to another surmise, that the regulators are acting in the way that supports the actual wish of the government – or the vested interest that it serves – as opposed to its stated policy commitments.

Through the Nigerian Oil and Gas Content Development Act of 2010, the government has been trying to increase local participation in the oil and gas sector. The Dangote Refinery currently employs 29,000 Nigerians. Once it is operating at full capacity, it is estimated that the refinery will employ over 57,000 people, with the majority of them being Nigerians. While this is an impressive contribution to local content development in the sector, one is not unaware that the combined local refining capacity in the country – if all the refineries are working – exceeds domestic demand and this may lead to investment and labour losses especially where external markets are not developed to absorb excess local production of petroleum products. This is a major challenge the government and the regulators should be trying to solve with the operational launch of Dangote Refinery. The regulators should also concern themselves with fair competition in the sector, using the socio-economic policy goals of the government as a lever.

According to the Corporate Finance Institute, the benefits of a mix economic system include efficient resource allocation, encouragement of innovation, and the ability to address market failures and social welfare concerns. The pursuit of these goals will not only strengthen the domestic economy, but it will also make it externally competitive. This is why countries that practice the system have significant export market contribution to the success of their domestic economies.

NNPCL’s insistence on continued importation of petrol into the country to serve a large market that can now be served with locally refined products is not supported by sound economic policy. Even though it is now a limited liability company, NNPCL has continued to undermine the principle of operational efficiency for which private sector businesses are noted, and which benefits the economy and the consumers. The government needs to act except if NNPCL is serving its unofficial interest.

To resolve this issue, the government should accelerate a credible and transparent process for the privatisation of the NNPCL. With private sector acquisition of a majority stake in the company, the government can then focus on effective regulation of the sector. This will provide an immediate financial windfall for the government. Over the long term, the government will also reap the financial gains of improved efficiency in the sector.

Jide Akintunde is Managing Editor of Financial Nigeria publications. He is also Director of Nigeria Development and Finance Forum.

This article is the lead feature in Financial Nigeria magazine, April 2025 print edition.

Other Features

-

What I learned after studying 80 innovation programmes in Africa

My team and I are in the process of designing an innovation and entrepreneurship programme which we hope accelerates ...

-

Nigerian power sector: resolving liquidity concerns

Given financial pressures on the power generation companies and distribution companies, upward tariff revisions ...

-

India has arrived

A founder of the Non-Aligned Movement, India has plenty of experience navigating precarious ...

-

The new CBN foreign exchange code and its implications

With the introduction of the CBN FX code, Nigeria has aligned with leading financial jurisdictions, such as the ...

-

FIRS: Tax revenue as Nigeria’s new ‘crude oil’

President Tinubu deserves to be hailed for the huge jump in the shareable FAAC allocations which has continued an ...

-

DeepSeek and the future of finance

The DeepSeek disruption is a clear signal that the AI landscape in financial services is about to undergo a seismic ...

-

How to sell USDT for cash in Nigeria: A comprehensive guide

Selling USDT for cash in Nigeria doesn’t have to be complicated.

-

A review of the national tax bills

The four tax bills signify a pivotal shift in Nigeria’s tax framework, focusing on critical areas of revenue ...

-

How Tinubu Deviates from IMF/World Bank reform recommendations

President Tinubu should not only adopt IMF’s policies, but he should also heed the recommendations for ...

Most Popular News

- Artificial intelligence can help to reduce youth unemployment in Africa – ...

- Nigeria records $6.83 billion balance of payments surplus in 2024

- Soaring civil unrest worries companies and insurers, says Allianz

- Tariffs stir inflation fears in US but offer targeted industry gains ...

- Tinubu appoints new Board Chair, Group CEO for NNPC Limited

- CBN net reserve hits $23.1 billion, the highest in three years

_-_300x350-202501141442143232.jpg)

_Charging__Power_Grid_-_300x350-202501141447571577.jpg)